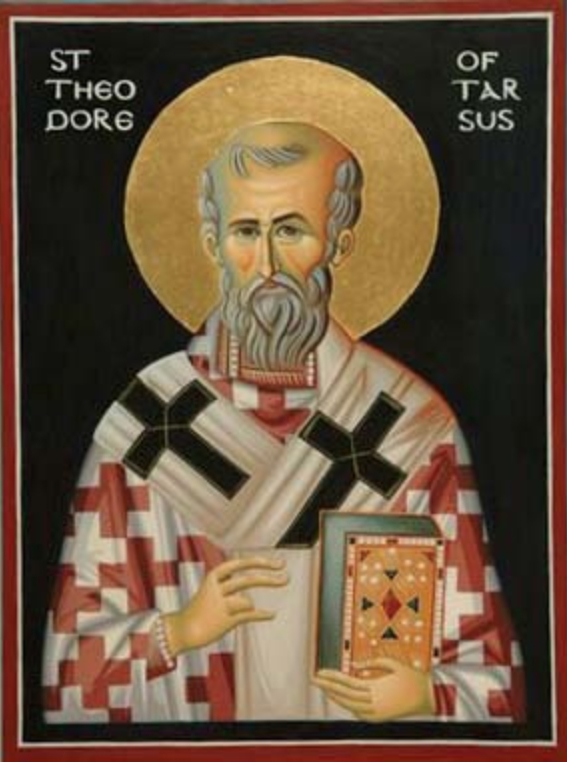

Saint Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury

by Aidan Hart

Saint Theodore, who lived from 602 until 690, combined in his person a remarkable spectrum of cultures and countries. He was a Greek from Tarsus of Cilicia, almost certainly studied in Antioch and Constantinople, later lived as a monk in Rome where he was probably involved with Saint Maximos the Confessor in the Lateran Council, became one of the most important Archbishops of Canterbury in Britain assisted by an African called Hadrian, and worked among the English and Celtic people for twenty-one years, dying at the age of about eighty-eight.

But Saint Theodore is not only remarkable in his own personal history, but also for his lasting imprint on the administration of the English Church, particularly in his restructuring of its diocesan system and in the canon laws which he established. He gave unity to a Church in tension between its British, English and Roman members, established a flourishing school in Canterbury, through local synods linked his British Church to the Church of Byzantium, and, as Bede says, was the first Archbishop of Canterbury willingly obeyed by all Anglo-Saxon England.

St. Theodore of Tarsus

This is a remarkable achievement, and yet the multi-ethnic Church of Theodore’s time is not so very different from the situation in Britain today. Through immigration of Russians, Cypriots, Serbians and others, the Orthodox faith is being reintroduced to this land. And English and Celts are becoming Orthodox to the point which, although still small, the Orthodoxy Church is the second fastest growing Christian group in this country. And so, as in Theodore’s time, we find the Orthodox Church in Britain today is a mixture of peoples from different countries. Theodore’s times and life are pertinent for us today.

Sources

Most of what we know of Saint Theodore from direct sources comes from the Venerable Bede (673-735) in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede naturally enough concentrates on that part of Theodore’s life spent in Britain, but does tell us a little of his life in Rome. There are fortunately also references in Theodore’s and others’ writings which have helped scholars form a likely course of events before and including his time in Rome. The most up to date scholarship is to be found in Archbishop Theodore edited by Michael Lapidge, in Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England II, Cambridge University Press, 1995. The most detailed work on his life is in Biblical Commentaries from the Canterbury School of Theodore and Hadrian, ed. B. Bischoff and M. Lapidge, CASS 10 (Cambridge, 1994), in pages 5-81. The following information of Theodore’s life is taken mainly from Lapidge’s article in Archbishop Theodore, pp. 1-29; references and quotes are taken from this article (referred to as Lapidge in the footnotes) unless otherwise noted.

Tarsus, Antioch and Edessa

Theodore was born in Tarsus in 602. We know from his career in England and Bede’s own words that Theodore was a scholar of some note, learned in a variety of subjects, “both in sacred and in secular literature, in Greek and in Latin” to use the words of Bede.1

Where did Theodore gain his education? Tarsus was the chief Greek city of the province of Cilicia, but despite this it seems that there was no school of advanced studies there – at least no records mention any. The nearest school for someone wishing to pursue studies was Antioch. Since Tarsus was within the Patriarchate of Antioch it is likely that Theodore went there to begin his studies. These two cities were linked by a major Roman road, and so travel was not difficult.

There is further evidence supporting the belief that Theodore studied at Antioch. The biblical exegesis of this school is known for its more literal, moral emphasis than the Alexandrian school, which tended to concentrate on the mystical, symbolic meaning of passages. The Biblical Commentaries of Canterbury which are attributed at least in part to Theodore, are definitely of the Antiochean interpretative school.

During Theodore’s time Syria was bilingual, using both Greek and Syriac. The centre of Greek language Christianity in Syria was Antioch, whereas that of Syriac language Christianity was Edessa, which is where many luminaries of the Church like Ephraim the Syrian (d. 373) lived. Again, the Canterbury Commentaries give us a clue as to Theodore’s possible movements at this early stage of his life. They suggest that as well as studying in Antioch he also at least visited Edessa. The relevant passage is so specific that it is surely an eye witness account:

Cucumbers and melons are the same thing, but cucumbers are called pepones when they grow large, and often one pepon will weigh thirty pounds. In the city of Edessa they grow so large that a camel can scarcely carry two of them.2

Three other clues in the Commentary strongly suggest a sojourn in Edessa, and even a knowledge of Syriac: three times the etymology of words is explained in reference to Syriac, Saint Ephraim the Syrian is quoted once, and there are parallels on a number of occasions with Ephraim’s commentaries and those of another, called The Book of the Cave of Treasures, both of which were not at the time available in Greek.

The Commentaries also include what appear to be first-hand observations of Persian life. This is accountable by the fact that the Persians conquered Syria over the period of our saint’s early life. (Antioch was taken in 613, and then Damascus and Jerusalem the following year when the true Cross was captured. Soon afterwards the Persians took Tarsus.) The Commentaries mention for example that the cups mentioned in Exodus 25:31 are “not round like a saucer, but long and angular; the Persians still use them for drinking in feasts” (PentI 303). This reads like a first-hand observation.

Constantinople

In 627 the Byzantine army under Heraclius finally defeated the Persians in Ninevah and recovered the Cross. But all these campaigns left his army too exhausted to resist the flood of Muslim Arab attacks over the 630’s. After a devastating defeat at Yarmuk near Galilee in 636, Heraclius abandoned Syria and Palestine to the Arabs, who went on to take Jerusalem and Antioch the following year. Syria and Palestine were subsequently no places for Christians to be, and they fled in great numbers to North Africa, Sicily, southern Italy, and Constantinople.

Theodore may have fled during the earlier Persian invasion, but a passage in the Commentaries hints that he had experience of the Arabic invasion and therefore that he fled in their time rather during the earlier Persian invasion:

…thus Ishmael’s’ race was that of the Saracens, a race which is never at peace with anyone, but is always at war with someone. (PentI 104)

If Theodore did leave at the time of the Arab invasion, then we can say that he probably left Syria in 637, when he was 35 years old. Where did he flee? Again the Commentaries provide the likely answer:

Theodore reports that in Constantinople he saw the Twelve Baskets woven from palm-branches and preserved as relics, which had been brought there by the empress Helena.

Although Constantinopolian schools never rivalled those of the great eastern centres of Antioch and Alexandria, it did experience a boon under the Emperor Heraclius (610-641) and Sergius, the Patriarch (610-638). During their reigns the university was particularly strong in medicine, jurisprudence, philosophy and astronomy. About the time of Theodore’s probable arrival, Constantinople had as teachers some of the greatest scholars in the Greek-speaking world, notably Stephen of Alexandria, Theophylact Simocatta, Sophronius, later Patriarch of Jerusalem, and his companion John Moschus, writer of the famous work The Spiritual Meadow.

We know for certain that Theodore was present in Constantinople, but is there evidence that he actually studied there? The range of interests and the knowledge expressed in the Canterbury Biblical Commentaries strongly suggests that he did. Theodore’s school at Canterbury taught Roman civil law, as St Aldhelm tells us, and Theodore’s own Iudicia and the commentaries show a good knowledge of Roman law, particularly as contained in Justinian’s Corpus iuris ciuilis. Now Constantinople was the chief centre of study for this subject.

Again the Commentaries show knowledge of rhetoric, and Bede tells us that astronomy and ecclesiastical calendar computations were taught at the Canterbury school. The Commentaries also deal in some detail with various medical subjects, and these often parallel Greek medical texts, such as Stephen of Alexandria’s scholia on the Prognostica of Hippocrates. The Commentary also shows knowledge of Greek philosophy, such as when the Latin word firmamentum in Genesis is rendered by the Greek word aplanes common among the philosophers and not by stereoma, as the Septuagint and Church Fathers render it. All these subjects were taught to some depth in the Constantinople university.

Rome

The next documented sojourn for Theodore is Rome. Bede tells us that Theodore was living as a monk there when he was chosen and consecrated by Pope Vitalian as Archbishop of the English 26 March, 668. His monastery was evidently one which followed eastern customs, for he was tonsured, “like St Paul, in the manner of the oriental monks.” Before his consecration as bishop, Theodore had to let his hair grow so that he could be tonsured with the Petrine coronal tonsure.

Which monastery was he in? We know of four oriental monasteries in Rome at the time – one Armenian, one Nestorian, one called Saint Saba’s for Palestinian monks, and finally one for Cilician monks. Theodore’s monastery is most likely to have been the Cilician one. First, he himself was Cilician, and second, it was named after Saint Anastasios and it is fairly certain that Theodore was the one who introduced this saint’s life to England.

It is highly likely that Theodore was involved with combating the monothelitic heresy while in Rome. This heresy compromised the union of the divine and human natures of Christ, since it taught that He possessed only one will- a divine will – and not two wills, a divine will and a human will as the orthodox taught.3 After the Persian and Arab invasions the centre of defence for the traditional position shifted from Palestine to Rome, mainly because of the orthodox stance taken by Pope Theodore (642-9) and Saint Maximus the Confessor, who was exiled there from around 655.

In 649 Pope Martin I (649-55) convened a council at the Lateran Palace, the socalled Lateran Council. But there was a problem in that the 105 bishops present were mostly Italian, and possessed little knowledge of the subtleties of the Greek terminology which was so crucial to an understanding of the monothelite controversy. So they had to rely heavily on the oriental monks present in Rome to advise them. They turned particularly on the saintly and learned Maximus.

But there is strong evidence that also Theodore played an important advisory role. Two things point to this conclusion. Firstly among the names of advisors listed in the Council’s Acts is one Theodorus monachus. Is this our Theodore? The entry is set directly after the list of abbots and priests, but, although he is a non-ordained monk, this “Theodore the monk” is set before the deacons. This suggests that he was an important advisor. Our Theodore we know was extremely learned and certainly would fit such a role.

A second and more telling piece of evidence supports the identification of this monk with our Theodore. Thirty-one years after the Council, when the controversy was still raging, Pope Agatho convened another synod at the Palace in order to gather the views of the western churches under his jurisdiction. The Pope opened the council by explaining that the issue was a complex one, and therefore needed a learned and deep thinker to clarify the issues at stake. He said there was only one such man within his church, and that was Archbishop Theodore: “We were hoping, therefore, that Theodore, our co-servant and co-bishop, the philosopher and archbishop of Great Britain, would join our enterprise, along with certain others who remain here up to the present day.” The natural explanation for this high regard of Theodore in Rome is that he was present and influential in the 649 Lateran Council.

An important implication of Theodore being involved in the monothelite controversy in Rome and in the Lateran Council is that he would have been in contact with St Maximus the Confessor.4 He also could well have known Saint Sophronius Patriarch of Jerusalem. Sophronius had been Maximus’s predecessor in the fight against monothelitism, and was in Constantinople some time in the 630’s – a period within which, as we have discussed, Theodore himself was also present in the City.

Theodore’s involvement in the Lateran Council would also explain Pope Vitalian’s concern, in the words of Bede, that Theodore ‘did not introduce into the church over which he was to preside anything contrary to the truth of the faith in the manner of the Greeks.’5 What was Vitalian referring to? At that time, 667, dyothelitisim (the orthodox doctrine) was still outlawed by the emperor Constans II; Pope Martin and Maximus had both been tried for treason because of their dyothelite stand and had died in exile. So the things “contrary to the faith” which concerned the cautious Vitalian were in fact in all likelihood the Orthodox doctrine of dyothelitism, then outlawed by the emperor.

To satisfy himself that Theodore did not go off the rails, Pope Vitalian had the African Hadrian go with him to Britain. Vitalian had originally asked Hadrian to become Archbishop, but Hadrian had refused and recommended Theodore in his stead. In reality Theodore of course held the Orthodox dyothelite position and not the royally sanctioned monothelite one.

So it was that in Rome Theodore was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury on 26 March, 668. He travelled with the African Hadrian, who knew Gaelic ways and so would be helpful when they travelled through Gaul, and the English monk Benedict Biscop who happened to be in Rome at the time. They arrived in England on May 27th 669. Thus began Saint Theodore’s incredibly energetic and fruitful twenty-one years of service as Archbishop of Canterbury.

England

Up to this point in Theodore’s life, scholars have had to depend on indirect evidence to form a picture. From now on things are more straight forward, since details are provided by the writings of Aldhelm, Bede and Stephen of Ripon. Moreover, scholars have begun to cast their net further than overt references to Theodore and are unearthing further information about his life and work through the study of other literature, like the Canterbury Biblical Commentaries to which we have already referred.

Among Theodore’s first moves on arrival in England was to appoint Benedict Biscop abbot of Saint Peter’s monastery in Canterbury. He then set out to travel throughout England with Hadrian.

Theodore saw that many sees were vacant – in fact, there appears to have been only four bishops left in the whole of England. The archbishopric had effectively been vacant for five years and the plague had killed many bishops. But empty sees were not the only problem. Most dioceses were unmanageably large. One of his most important tasks was therefore not only to fill the vacancies with suitable men but to reorganise the whole diocesan system.

The synod of Hertford: Theodore as administrator

In 673, some four years after his arrival in Britain, Theodore called a national council at Hertford. It must be noted that this was not a sizeable episcopal gathering, as would normally be the case if such a council had been called in, say, Gaul. The synod’s account in fact lists only five hierarchs besides Theodore: Bisi, Putta, Eleutherius, Wynfrid and Wilfrid represented by proxy. Admittedly Bede does say that also present were “many other teachers of the Church who both understood and loved the canonical statutes of the Fathers.” But is was nonetheless a meagre and challenging beginning for such a large archdiocese.

The council’s acts first affirm the bishops’ belief in the teachings of the apostolic Church. On a more administrative level it goes on to promulgate ten laws on church practice, namely when Easter should be celebrated (according to the system agreed at the Council of Whitby held ten years earlier), that a bishop should confine his authority to his own diocese, that he should not interfere in the monasteries, that monks should not wonder from monastery to monastery, nor priest from bishop to bishop, that a synod be held yearly, and that more bishops be consecrated as the number of believers increases. There are also various rulings on marriage.

This council began Theodore’s thrust to bring peace and unity among the various personalities and traditions which had hitherto weakened the Church in Britain. More so than the first Archbishop of Canterbury, Augustine from Rome, Theodore had a vision for an indigenous British Church . While being strict in doctrine and the keeping of church canons he was flexible with regard to customs. It was only under his leadership that the English, Celtic and Roman Christians really united in Britain. Three factors helped him to achieve this. As someone from a culture not represented in Britain he was less likely to be held in suspicion as preferring per se the Celtic, English or Roman parties. Second, his life in various cities of the eastern Mediterranean and on the Continent had exposed him to a wide variety of cultures, and this saved him from absolutising the customs of any one people. Third, he had that wisdom and discernment which comes more easily with age – he was sixty-six when he arrived in England

Theodore consecrated bishops to fill vacant sees, but more importantly, he subdivided overly large dioceses. In doing this he bypassed the identification of a temporal kingdom with a diocese and thereby helped to free ecclesial life from secular interference. He was nevertheless careful not to have a diocese spreading across more than one kingdom, something which would have created unnecessary friction. He centred each dioceses on a city or major centre, and in so doing reverted to an older, more traditional church practice.

Generally his policy of subdivision went smoothly, except with Wilfrid and his enormous region of all Northumbria. Over Wilfrid’s head, from 678-81, Theodore subdivided the see into four. This amounted to virtual deposition, and Wilfrid appealed directly to Rome to be reinstated. The papacy ruled in Wilfrid’s favour but king Ewgfrith of Northumbria refused to comply and imprisoned Wilfrid, on condition that he be freed only if he left his kingdom. Eventually a compromise was reached in 686 when Theodore reinstated him at Northumbria, but with reduced jurisdiction.

As noted, at the first synod of England held in Hertford in 673 there were five bishops represented. By the end of the decade there were twelve bishops in England. But the issue is not only numbers, for Theodore was careful to choose bishops for the holiness of their lives. Indeed many of those whom he consecrated came to be venerated as saints, namely Cuthbert, Erkenwald, John, Eata, Bosa and Trumwine – and Chad too if we discount his earlier suspect consecration. One salient feature of Theodore’s candidates is that they were all monks, whereas in Gaul married bishops were common at the time. This latter practice sometimes led to the abuse of inherited bishoprics.

Theodore desired his bishops to work together, as shepherds ultimately of one flock. To this end he encouraged them to gather together when they could, and not only at the planned two yearly synods, but at events such as episcopal consecrations. At Saint Cuthbert’s consecration for example, there were no less than six bishops present. Theodore also called local synods, such as those at Burford in 679 and at Twyford in 684.

The Synod of Hatfield

Another council was called by Theodore in 680, at Hatfield. This assembly was occasioned primarily by the arrival of Abbot John from Rome, who had been sent by Pope Agatho to see if Britain “was free from contamination by heretics”,6 particularly the monothelites. The council members affirmed their faith in the Creed and the teaching of the five ecumenical councils and of the accredited doctors of the Church. It also made special mention of the Lateran council held by Pope Martin, which had upheld the orthodox dyothelite teachings.

Mention must be made of the Hatfield synod’s inclusion of the filioque clause into the Nicene Creed, namely that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.7 This was an addition to the original Creed which was condemned as heretical by later orthodox statements but which was eventually accepted by the West.

How did Theodore interpret this word filioque, and why did he have it included? Paradoxical as it appears, Theodore probably came to accept the filioque through contact with that acclaimed orthodox Father of the Church, Saint Maximus the Confessor, whom we know accepted the validity of the word. But the other question is whether or not Theodore, and Maximus, understood filioque to mean that the Spirit proceeds eternally from the Son or that He was sent in time through the Son. The Greek contemporary theologian Fr. John Romanides argues that they supported the latter interpretation. Certainly the inclusion in the Hatfield’s Acts of the phrase “One God subsisting in three consubstantial Persons of equal glory and honour” affirms that the filioque was not intended to relegate the Holy Spirit to a lower position than the Father and the Son, something which the Orthodox say the filioque does when understood as eternal procession.

Theodore and Canon Law

It was mainly as a gifted administrator that Saint Theodore had the most profound effect on the English Church. As Bede was able to say of him: “The churches of the English made greater progress during his pontificate than they had ever done before.”8 He had a great knowledge of canon law from his studies in Europe, but also knew how to apply them with pastoral wisdom. In his account of the Hertford Synod he writes that “I produced the said book of canons, and publicly showed them ten chapters which I had marked in certain places, because I knew them to be of the greatest importance to us…”9 That is, he knew how to apply canons with discernment. The Iudicia is another work come down to us under Theodore’s name. We do not have it in its original form, in Theodore’s own words, for it has gone through two editors, but what we have certainly owes a great debt to him. It reveals a deep knowledge of early church councils.

But besides showing knowledge of existing Greek and Latin canons and practices, Theodore’s own decrees contained in the Iudicia had a considerable influence on future canon law, particularly through what is known as “Theodore’s Penitential” which is contained in the first part of the work.. Although not itself written by Theodore but by others some years after his death, the Penitentials undoubtedly contain decrees established by him. This Penitential is a kind of medicine chest, which prescribes private penances for various sins. It came to be influential both in Ireland and on the Continent, most notably in introducing the practice of private confession. It shows a lot of influence from Greek penitential literature, for example in the distinction between the strict application of a rule (akrivia in Greek) and a degree of leniency when this would best further the salvation of an individual (oikonomia).

The school of Canterbury and sacred chant

Another achievement of Theodore was to establish the school at Canterbury. This made available a great range of subjects both sacred and secular, and exposed England to learning forged in the East. This he set up with the help of his companion Hadrian. It even attracted students from Ireland. It taught Latin, and very rarely for his time, Greek, as well as Roman Law, poetic metre, computistics (the calculation of the church calendar), music, astronomy, church singing and biblical exegesis after the form of the Antiochean school.

The school and Theodore’s policy of education had far reaching effects. Among the school’s future lights was Saint Aldhelm, and Bede himself attributes his own learning back to Theodore’s school.

Bede tells us that through the school “knowledge of sacred music, hitherto limited to Kent [where Saint Augustine of Canterbury had begun his mission], now began to spread to all the churches of the English.”10 An important impetus to the teaching of Roman chant was given by the arrival in England of John the Arch-cantor of St Peter’s in Rome, and Abbot of the monastery of Saint Martin. He was sent by Pope Agatho to go with Saint Benedict Biscop to Britain “where he was to teach [Benedict’s] monks the chant for the liturgical year as it was sung at Saint Peter’s, Rome.”11 He taught the monks the theory and the practice of chant and liturgical reading, and wrote down the typicon or way of celebrating the liturgical year. Bede tells us that many copies were made of this document and that proficient singers came from other parts to learn from him and that he himself accepted invitations to go and teach elsewhere.12

Theodore as peacemaker

We have seen that Theodore brought unity among the bishops and their dioceses, but he also brought peace between kings. After the battle of Trent in 679 he reconciled king Egfrid of Northumbria and Ethelred of Mercia, and thus avoided a war which would have ruined the North.

Saint Chad

Although Theodore was intent on re-organising the Church in England and could be strict in applying the canons in order to correct abuses, he was not inflexible. This is illustrated in his treatment of Saint Chad. To use Bede’s own words:

When Theodore informed Bishop Chad that his consecration was irregular13, the latter replied with the greatest humility: ‘If you know that my consecration as bishop was irregular, I willingly resign the office; for I have never thought myself worthy of it. Although unworthy, I accepted it solely under obedience.’ At this humble reply, Theodore assured him that there was no need for him to give up his office, and himself completed his consecration according to catholic rites.14

Around 669 Theodore removed Chad from York and restored Wilfrid to this his rightful see. Chad, after a period at the monastery of Lastingham, was appointed by Theodore to be the first bishop of the Mercians and the people of Lindsey. This opening in the hitherto pagan Mercian kingdom (approximately present-day Midlands) was due to its new king, Wulfhere, being a Christian.

Chad’s episcopal seat was at Lichfield, where his relics were until the reformation. He founded a monastery at Barrow in Lincolnshire on land given him by Wulfhere for that purpose, and another near the cathedral of Lichfield. Although his episcopate lasted only three years, until his death in 672, he was revered as one who “administered the dioceses in great holiness of life after the example of the early Fathers.”15

Bede relates a moving incident which illustrates the humility of both Theodore and Chad. Chad preferred to visit his flock on foot rather than on horseback, no doubt following the example of his spiritual father, Saint Aidan. Theodore ordered him to go by horse for long journeys, but Chad was reluctant to change his cherished practice. But the arch-prelate, now in his seventies, was insistent, and considering it “proper for him to ride, himself insisted on helping him to mount his horse.”

Theodore’s wisdom is evident in his choice of Saint Chad to found this diocese, for in Chad was a living connection between the English and the Celtic Christians. From childhood Chad was a pupil of Saint Aidan’s school at Lindisfarne, in Northumbria. Aidan was Irish and was a monk in the monastery of Iona off the West coast of Scotland, a monastery established by that great Irishman Saint Columba. Aidan was sent to Northumbria as its bishop and missionary in response to a request from its newly enthroned English Christian king Oswald. One of Aidan’s first deeds was to establish a school for English boys, it would seem with the intent of building up an indigenous mission. Indeed at least four of the pupils, Chad and his brother Cedd included, became outstanding bishops. The third abbot of Lindisfarne, the English Cuthbert, was also consecrated bishop by Theodore, around 685.

Britain and the East

Was Theodore’s influence in linking Britain more firmly with Mediterranean Christianity a novel thing? By no means. The following are some examples which show that there were lively contacts between the two cultures, mainly via Gaul.16 The monastery of Lerins in southern Gaul sustained lively contacts with Egypt, and it was largely from Gaul that Britain learned its monasticism, and indeed its faith. Although it may be spurious, one tradition associates Saint Patrick with the great Saint John Cassian, who was educated in Bethlehem and trained in monasticism in Syria and Egypt. Saint Jerome, living in Bethlehem, continued a lively correspondence with people all over the Continent, including those in Marseilles, with a monk Sysinnius acting as postman, as well as tale-bearer!

But there was not only a second-hand Syrian influence in Gaul, there were actual Syrian monks living there. Their monasteries flourished particularly around 450, and continued for another two hundred years. In the fifth century Sidonius Apollinaris records an epitaph over the grave of one Saint Abraham, who was born in the Euphrates, suffered during the persecution of Persian Christians under king Isdegerdes, then migrated to France where he died as abbot of a monastery. At Treves in Eastern Gaul have been found Chaldean and Syrian inscriptions. Going to a later period, the acts of the council of Narbonne held in 589 included in its orbit the Goths, Romans, Syrians, Greeks and Jews living in Narbonne.

Evidence of more direct contact between British and the Syrians is afforded in the life of Saint Columba: we are told that after being evicted by the ruler of Burgundy, the only sympathy Columba found in his near starving state was from a Syrian woman. “I am a stranger like yourself,” she tells him, “and come from the distant sun of the east, and my husband is of the same race of the Syrians.”

The near contemporary life of Saint Simeon the Stylite (died 459) mentions that people came to see him from all over the known world, and among the list of such countries mentions Britain. Another instance of direct contact, although not necessarily between Christians, is described in the life of Saint John the Almsgiver, Patriarch of Alexandria, where we are told of a trading vessel which goes to Britain from Alexandria.

What of eastern Europeans other than Theodore living in Britain? Chroniclers mention three. They tell us of a Greek monk named Constantine living in Malmesbury, a Greek bishop in Ely who was close to the Court of St Edgar, and a hermit from Antioch, Saint Simeon, who preached in England about 983.17

Theodore’s repose

Theodore died on 19 September, 690 at the age of eighty-seven. He was buried close to the first Archbishop, Saint Augustine, in the monastery of Saints Peter and Paul, Canterbury. In 1091 his body was found to be incorrupt and was translated. He was evidently regarded as a saint earlier than this, since he is included in Saint Willibrord’s calendar (658-739). This calendar was written for Willibrord’s personal use, and the extant copy dates from his time since it includes entries in his own hand.

No biography was written of Saint Theodore until the late eleventh century, and there were no miracles attributed to him, hence perhaps his relative obscurity. It has only been in the last ten or so years that this great saint has begun to emerge from the mists of time. Although his spiritual gifts of administration are not as immediately spectacular as miracle working, the fruits of his labours are no less profound. But he was more than a charismatic administrator. He was large-hearted. The one man with whom he had to struggle against most in his reorganisation of dioceses, namely Wilfrid, was the one whom, according to Wilfrid’s biographer, Theodore wished to succeed him at Canterbury.

Aidan Hart

www.aidanharticons.com

———————————————————-

“Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting: Egg Tempera, Fresco, Secco” by Aidan Hart.

The most comprehensive book to date on the techniques of icon, egg tempera and wall painting. Chapters include the history and theology of the icon, methods of panel making, gesso, gilding, and pigment preparation, colour theory, icon design, the proplasmos and membrane techniques of egg tempera painting, and fresco and secco painting.

• Over 450 colour illustrations and 160 drawings.

• 460 pages. 227mm x 278mm.

• Hard cover, £40. Post free in the UK when ordered through the website: