Embroidered Icons

by Juliet Venter

It is one of my hobby horses that embroidery has become the poor relation of the liturgical arts, and a glance at the textiles in use in many churches makes it plain why that is so. So when a new acquaintance passed me a back issue of this Review I was not surprised to read a sharp comment about students of iconography who rush through a week of icon-painting “as though it was something akin to an embroidery course”. The worn remains of an embroidered hanging on display at the Byzantium exhibition are a reminder that embroidery served the rites of the church more honourably in previous days. The textile output of the imperial workshops, of which so little survives, must once have rivalled the other arts in magnificence and skill. An icon image may be rendered in embroidery just as well as painted, carved, enamelled or made in mosaic, but it is a medium especially vulnerable to that famous corrupting moth – not to speak of damp, candle smoke, atmospheric pollution, damage from careless handling, and the natural characteristic of silk to crack and perish with age.

It is one of my hobby horses that embroidery has become the poor relation of the liturgical arts, and a glance at the textiles in use in many churches makes it plain why that is so. So when a new acquaintance passed me a back issue of this Review I was not surprised to read a sharp comment about students of iconography who rush through a week of icon-painting “as though it was something akin to an embroidery course”. The worn remains of an embroidered hanging on display at the Byzantium exhibition are a reminder that embroidery served the rites of the church more honourably in previous days. The textile output of the imperial workshops, of which so little survives, must once have rivalled the other arts in magnificence and skill. An icon image may be rendered in embroidery just as well as painted, carved, enamelled or made in mosaic, but it is a medium especially vulnerable to that famous corrupting moth – not to speak of damp, candle smoke, atmospheric pollution, damage from careless handling, and the natural characteristic of silk to crack and perish with age.

Only the skill of the restorer enables us to glimpse that magnificence today. In honour of the fine art of embroidery and its service to iconography, I would like to share with Icon readers my recollection of an extraordinary exhibition of both embroidered and painted icons from the Stroganov school which I was privileged to happen upon in an outlying district of Paris way back in 1991. The Stroganovs were a wealthy dynasty of merchants and business speculators who were notable patrons of the arts and donors to the Russian church from the late 16th to early 18th centuries. The family maintained icon-painting workshops in their home town of Sol’vytchegodsk, and an embroidery workshop until the beginning of the 18th century which was personally overseen by successive great ladies of the family.

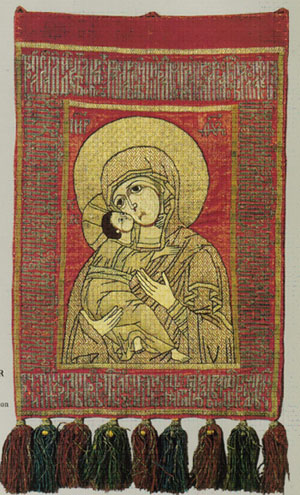

The embroideries which I saw in Paris had been restored at the famous Igor Grabar Centre in Moscow and largely dated from the 16th & 17th centuries. The embroidered icons included in the exhibition ranged from miniature work on vestments, stoles and chalice veils, to large hangings for the iconostasis, banners for processions, full-figure tomb-covers and of course several magnificent Good Friday epitaphioi with the body of Christ in the tomb mourned by angels and saints. Whilst these embroidered icons followed the same rules and patterns as a painted one, the technicalities of the medium obviously dictated a more graphic, even decorative, style. Each piece was necessarily a collective interpretation of the artist’s original drawing, which tended to result in greater individuality in each rendition of a subject and more variation in style from the original conception.

To begin with an artist or limner painted the outlines of the design on the ground cloth (often a Venetian damask silk), which was then mounted on a linen backing and stretched in a frame ready for working. A workshop manager was responsible for the choice of colours and quality of materials employed, and also for maintaining a strict standard of workmanship. A team of specialist embroiderers worked simultaneously on each commission. Together they filled in the design, interpreting colour, line and shadow as the medium and materials permitted. It depended on the skill of the embroiderers (who would have served long apprenticeships and learned to make their work indistinguishable from that of their team-mates) whether the fluidity of line and expressiveness of the artist’s original drawing was preserved, a very difficult task in the medium of metal thread embroidery.

Many of the icons I saw were solidly stitched in gold thread, using couching thread in monochrome or restrained palette and relying very little on the colour or pattern of the ground fabric for their effect. Halos, clothing, lettering, scenery and sometimes the background, were rendered in surface-couched gold threads applied in miraculously small and intricate basket-weave or herringbone patterns, adjacent areas demarcated by contrasting stitch patterns. The faces, hands and hair were worked solidly in split stitch using naturalistic shades of silk, the stitching lines sometimes following facial and body contours to give a relief modelling effect. Shading was rendered in a very stylised and linear way, giving a startlingly graphic and abstract appearance to the faces. Another important characteristic of these pieces was the large embroidered borders with stylised lettering designs (giving festival or saints’ titles, and hymns or prayers appropriate to the liturgical festival), reminiscent of Islamic calligraphic art in their intricacy.

Some icons were further embellished with gems or many tiny pearls. The technique of this embroidery is very exacting and laborious, taking more than an hour to cover a square inch, so that a large epitaphios or tomb cover might be three years in completion in the Stroganov workshops. (Several of the items on display had donor inscriptions on the back which meant their start and finish dates could be accurately documented.) One can only wonder that it did not take longer, given the length of the winter in northern Russia and the difficulty of working with sparkling thread by lamplight. The length of the labour and the immense cost of the materials meant that workshop output was much smaller than for painted icons, leaving us with an even more diminished notion of their importance as religious artefacts. The defining characteristic of these embroidered icons, beyond the superficial richness of the materials, is the play of light and shade created by the sheen of silk and the contrasting directionality of the gold threads. Although the embroidery techniques employed bear some superficial comparison with those of opus anglicanum, that great medieval English export, stylistically they are very different.

Looking afresh at the exhibition catalogue, and especially at the figures of saints and the Virgin Hodigitria, it strikes me again that although the divine light emanating from the holy figures is quite differently expressed in embroidered and painted icons, these examples convey in a remarkable way the quality of powerful stillness and other-worldly presence we find in a great icon painting.

Julie holds weekly classes in her home al Letchworth.

Please visit my website at: www.juliet-icons.co.uk