By Fr. Silouan Justiniano

In Aidan Hart’s new book, Festal Icons: History and Meaning, we find a major contribution to the current icon revival, one which will be hard to surpass for many years to come. It is an impressive volume, not only in its size and bulk — measuring 28cms x 23cms and weighing 2.3 kilos, and consisting of 456 pages— but more importantly in its almost encyclopedic scope, demonstrating Hart’s thorough research and depth of theological insight. The book is also a landmark in so far as it augments the study on the Great Feasts to be found in the classic volume by Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, The Meaning of Icons. What the latter dealt with only briefly, in potential, Festal Icons delivers in actuality, in full panoramic scope and attention to detail. In this sense, without undermining the unique importance of the former work, it is bound to become a classic in its own right.

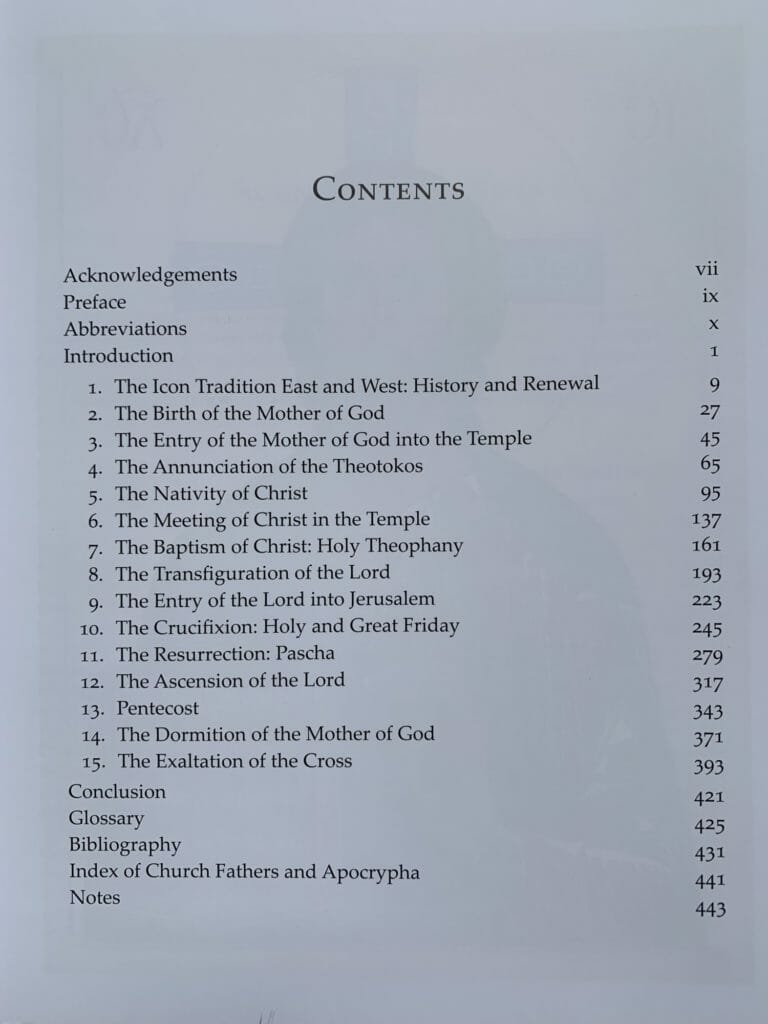

As the title suggests, the book focuses on an in-depth study of the iconography of the Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church. These are usually considered to be twelve in number (Dodekaorton in Greek), but with the addition of the Crucifixion and Resurrection, also called the ‘Feast of Feasts,’ they could be said to add up to fourteen major great feasts. The Dodekaorton proper is composed of eight feasts dedicated to Christ and four to the Mother of God. Each chapter of the book in turn focuses on a single feast, presenting a synthesis of current scholarship in a manner approachable to beginners and enriching to more seasoned iconographers.

The introduction focuses on laying the hermeneutical groundwork, giving us the theological framework for a correct approach in our interpretation of the feasts. This takes into consideration both Holy Tradition and rigorous historical research, which Hart weaves together seamlessly into a rich and inviting tapestry throughout the book, always with an air of prayerful devotion. The topics discussed in the introduction include liturgical time, commemoration as sacrament, typology, festal hymns, apocryphal sources and the format of the book.

The first chapter, titled “The Icon Tradition East and West: History and Renewal,” sets the study to follow “within the historical context of icons in general” (6), and serves as an insightful and useful summary of the history of the icon, from the earliest centuries of the Church, through the recent 20th century revival, up to the present day. It contains an important section on early Western iconography, wherein Hart discusses the influx of migrating tribes into western regions (from around 300-800), which precipitated a process of cross-cultural fertilization between tribal, Roman, and Byzantine artistic sensibilities. Within this context Hart takes the opportunity to focus on Anglo-Saxon England as a paradigmatic example of indigenous creativity within the living tradition of iconography. Towards the end of the chapter, he notes an often-undermined fact: “…Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, Carolingian, Ottonian, and Romanesque Church art is all inspired by a similar ethos to the Byzantine icon tradition. They are of the same family” (24).

In the first chapter, however, Hart also discusses the different approaches towards icons and imagery that developed in the West, prior to (e.g. images as primarily didactic tools, Libri Carolini, mid-790s) and after the Italian Renaissance (e.g. naturalism, perspective, sentimentalism, artistic subjectivism). He treats East-West tensions very skillfully, without a combative or excessively polemical tone, but rather with a more dialogical and charitable approach. This tactfulness extends to the rest of the book. Thereby he helps to clarify the differences and misunderstandings which exist between the Orthodox and Roman Catholics, regarding, for example, the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception (58-60), the Dormition of the Theotokos (376), and the juridical emphasis on the Crucifixion in the West, as compared to the maintained inextricability between the Cross and Resurrection in the East (292-294).

The feasts are studied according to their historical ordering of events, rather than their placement within the liturgical year. Each chapter (chap. 2-15), focusing on one of these Great Feasts, follows a consistent structure throughout the book, with only a few exceptions. In the beginning of the chapter, after giving the specific date of the celebration, Hart proceeds to contextualize the feast liturgically, by providing from the outset the hymnography (troparion and kontakion) and scriptural readings for Great Vespers, Matins and Liturgy. He then introduces the study of the feast by treating its background, the history of the feast, and the development of the icon. This material is followed by an analysis of a specific icon. In Hart’s estimation the chosen icon serves as an example of culminating achievement of many centuries of artistic effort in encapsulating the iconology of the feast and in embodying successfully its most salient theological themes.

The analysis of the icon first tackles the composition, both in regards to its narrative and formal components. To better elucidate his formal considerations, Hart provides photographs of the icon with overlapping linear diagrams, which serve to make more explicit its geometric substructure and rhythmic movement. Through this kind of formal analysis Hart unveils the icon’s theological significance, otherwise gone unnoticed by most viewers, undergirding and woven into the more obvious narrative components. Hart then moves on to analyze in detail all the various features which come together to make up the composition, whether these be the main characters of the narrative and their interaction, the use of drapery and architecture, furnishings and objects, landscape, animals and plants, or the specific use of color. These are all given close consideration, in light of hymnography and Scripture, as symbolically contributing in their own way to the overall theological significance of the icon.

This structure allows Hart to maintain clarity and focus, while elaborating to various degrees of depth complex theological themes pertinent to a given feast. He does this seamlessly, with elegant prose and an accessible style. Some of the themes elaborated in excursus are creation as a form of incarnation (91); the doctrine of the logoi (60-61); the healing of the five divisions (92-93;115-16); cataphatic and apophatic theology (86-89); essence and energies distinction (198-99); the three faculties of the soul (54); and the stages of purification, illumination and union (54).

The feasts are treated not just as mere historical moments within the divine economy, but rather as personally pertinent for us today, since they help us enter into the mystery of our own spiritual struggle toward deification. Through the feasts we experience “God’s action within created time,” its opening “towards eternity” (426). This touches on Hart’s emphasis on the difference between liturgical time (kairos) and chronological time (chronos). The former denotes “action and the right time” (426), the qualitative connection of past Sacred events with the ever-continuing activity of God in the present, while the latter designates the quantitative fragmentation of fleeting moments of created, temporal existence. This theme, with which Hart opens his introductory chapter (1-2), is picked up once again in the conclusion focusing on the feast of the Indiction, celebrated on September 1st – the first day of the liturgical year in the Orthodox Church. Thereby Aidan Hart underlines the significance of the Great Feasts, which both remind and bring us sacramentally into direct contact with the mystery of the sanctification of time, accomplished through the Lord’s economy of salvation.

For those unfamiliar with some of the Orthodox theological and liturgical terms used through the book, a five-page glossary is included in the back (425-29), defining terms such as nous, logoi, oikos, apolytikion, etc. This is followed by a bibliography of patristic translations, primary and secondary sources, for those interested in continuing further research. Furthermore, Hart provides a useful tool in the Index of Church Fathers and Apocrypha, prior to the end notes, making it possible to find specific passages used from these sources in the body of the text. A general index would have been a welcome addition to complete this helpful apparatus.

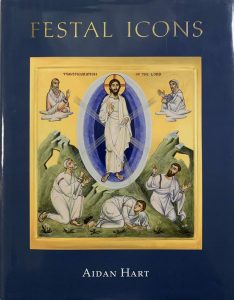

At present, the book only comes in glossy hardcover, with dust jacket. Both the front and back covers are illustrated with samples of Aidan Hart’s icons, the Transfiguration on the front and the Anastasis (Resurrection) on the back. The text on each page of the book is arranged in two-column format, with easily readable font size. The book is generously illustrated with 320 high-quality color photographs, of both historical work and contemporary icons, mainly examples of Aidan Hart’s own work. Furthermore, it documents the development of festal icons through a variety of media, not only portable icons, including mosaics, illuminations, stone and ivory carvings, embroideries and frescoes.

This elegant volume is a must-have reference for the library of any aspiring and professional iconographer alike. Scholars will not find it superfluous to consult or to include in their bibliographies. It should also find its home in parish libraries, East and West. For it will in fact be found most beneficial—not only by iconographers and professors, but also by parishioners, catechists and priests—as a devotional volume and research supplement for the preparation of classes and homilies. We can only be extremely grateful to Aidan Hart’s generosity in dedicating so much work, time and effort to see this volume come to full fruition. It will be put to good use for generations to come.

August 14th, 2022